I sat with Judy Wood at her dining room table in Tucson while we unpacked a box crammed with mementos from her earlier life in Slidell, Louisiana. We took out, among other miscellaneous papers, piles of crumbling newspaper clippings, an album that carefully documented her only campaign for office in 1978, a handwritten list of her campaign expenses, and handfuls of her wooden “nickels” that she gave out while canvassing her neighborhood. It was unassuming, but that box was a treasure trove documenting one of the greatest small-town political transformations in the South, in my humble opinion.

I had heard bits and pieces of what happened in Slidell from her before. I met Wood seven years ago when I joined the League of Women Voters of Greater Tucson, and she has been a mentor to me, teaching me all about political organizing, leadership, and building a welcoming organization. I had heard many of her stories about Slidell before, but this time, I wanted to know the whole story as best as she could remember. I asked her to start at the beginning.

“My husband was an oral surgeon,” she said, explaining how his profession led them to Slidell. Bert Wood had just been offered a job with LSU School of Dentistry at Charity Hospital in New Orleans, where he would teach oral surgery to LSU dental students. When he told her they were moving to Louisiana in 1973, Judy Wood was not happy. Their children, Peter and Marcy, were five and four years old, and just about to start school. For the past few years, they had been living in Iowa City, a liberal bastion in the Midwest where Bert was a resident of oral surgery.

Wood had grown up in Toledo in a Lutheran family that believed deeply in service to the community. She had graduated from Earlham College, a Quaker institution with students and faculty who had actively supported the civil rights movement. She had briefly taught math in the public schools. In Iowa City, she had quickly made friends and joined many organizations. Wood was the kind of woman who not only had great ideas but also made them happen.

Wood knew how she and her family would be perceived in Louisiana: outsiders, Yankees, and maybe worst of all, she was a moderate Republican like her father was. Bert told her they would only be there for three years, and then they’d figure out where they really wanted to live. “Well,” she said, “we went down there, and New Orleans was just a nightmare for me. I mean, at that point, I didn't understand the people. The public schools were abominable. You had to sign your kids up for the schools when they were in utero. And we weren’t Catholic.”

When they came to visit before the move, a colleague of Bert’s suggested they look at houses in Slidell. The small town’s major employers were its lumber yard and brickyard until it became a crossroads for three interstates. People were starting to move there to commute daily into New Orleans, driving on I-10 across Lake Pontchartrain. Hundreds of Martin Marietta employees and their families were moving to Slidell from Denver to work at the company’s new aerospace facility in Michoud. The city was rapidly becoming a bedroom community for New Orleans, and a lot of longtime locals were not too happy about it.

The first friend Wood met after unpacking her new house in the Broadmoor neighborhood in central Slidell was Pat Hedges, who moved around the corner from her two weeks later. “She's the one that decided we were going to study the South, so we started reading Faulkner,” Wood laughed, bemused at their earnestness in hindsight. Hedges would later go to law school after her children grew up, and eventually was elected the first woman judge of St. Tammany Parish. At the time when these two women moved there, Slidell still had a very insular small-town feel. In a profile for the Picayune, Hedges remembered, “I didn’t find the atmosphere in Slidell very stimulating. People here didn’t want you here, and they would tell you so. You don’t like it, go back to where you came from.” The newcomers, as they were called by Slidell’s locals, largely turned to each other for friendship and support.

Wood was appalled at Slidell’s tiny, underfunded, segregated libraries, which required her to submit the names of two male references before they would give her a library card. She started volunteering in the school system, working with fourth graders who were behind their peers in reading. The white, middle-class families who had moved to Slidell from other parts of the country were shocked to discover that there were no publicly funded activities in the summer for kids, not even parks or swimming pools. Most of these facilities had been closed across the South in retaliation to federally ordered integration (if they had ever had them to begin with). The only sports programs offered in Slidell were little league football and baseball for boys, which she knew was unfair to her daughter and the other girls of Slidell. In the summer of 1974, Wood and other women in the neighborhood started their own program called Summer Fun. In the following year, it was integrated and moved to the library. It offered movies, plays, crafts, and sports and was open to any child who wanted to come.

In 1974, the Slidell City Council voted to approve substantial raises for themselves and the mayor without informing the public beforehand, setting off a firestorm of controversy. Citizens demanded a new city charter, hoping it would put an end to, or at least reduce, the corruption in city government. The following year, an attorney for the local police union accused the police chief, Ed Schilleci, of wiretapping and misusing city funds. In Louisiana, sheriffs are political powerbrokers, and a corrupt one is especially dangerous.

When seven police officers assisted police union officials and two city councilmen with taking evidence from the police station, they were fired by Schilleci in retaliation, setting off a recall election. The City Council still paid the fired officers, and Schilleci was indicted after he was recalled. Larry Ciko, who covered Slidell for the Times-Picayune in those years, declared in his column, “There has never been a more chaotic time in the history of Slidell than now.”

Louisiana has always been known as one of the most corrupt states in the country. Even so, there was much to be outraged about in Slidell. Wood and her new friends started going to City Council meetings and joined the Broadmoor Neighborhood Association and the local League of Women Voters, where she met Cam Postle, an older woman who would mentor a new generation of women in Slidell and educate them about Slidell and its government. Both the newcomers and old-timers knew that something had to be done to reform Slidell’s local government. But who exactly would step and lead the charge was unclear.

The new city charter, championed by the Slidell Homeowners’ Federation, included a restructured City Council with seven of the nine seats based in newly drawn districts. Since all the Council seats had previously been at-large, the same white men were elected for years or even decades. Slidell voters had never elected an African American, a newcomer, a “damn Yankee,” or a woman to the Council.

In 1978 as the City Council election approached, Wood read the paper each morning to see who had declared to run from District E, which covered her neighborhood. The day before the qualifying deadline, Jack Throop, her friend and fellow member of the city’s planning commission who was running in his own district, called Wood and said, “You need to run. If you don’t run, you’re going to get the person in your district you deserve.”

She thought back on the moment and what made her decide to do it. “We were all appalled,” Wood said. “There were a lot of people in Slidell who didn't like the way the government was, but they weren't going to take it on. They didn't have the energy.” A lot of the women who had recently moved to Slidell were college graduates, but they didn’t work outside of their homes. Once their kids were in school, they had some time on their hands, and they had a vision for how things could be better. “So, we organized,” Wood said with a shrug. “They didn't know what hit them when all these new people came in.”

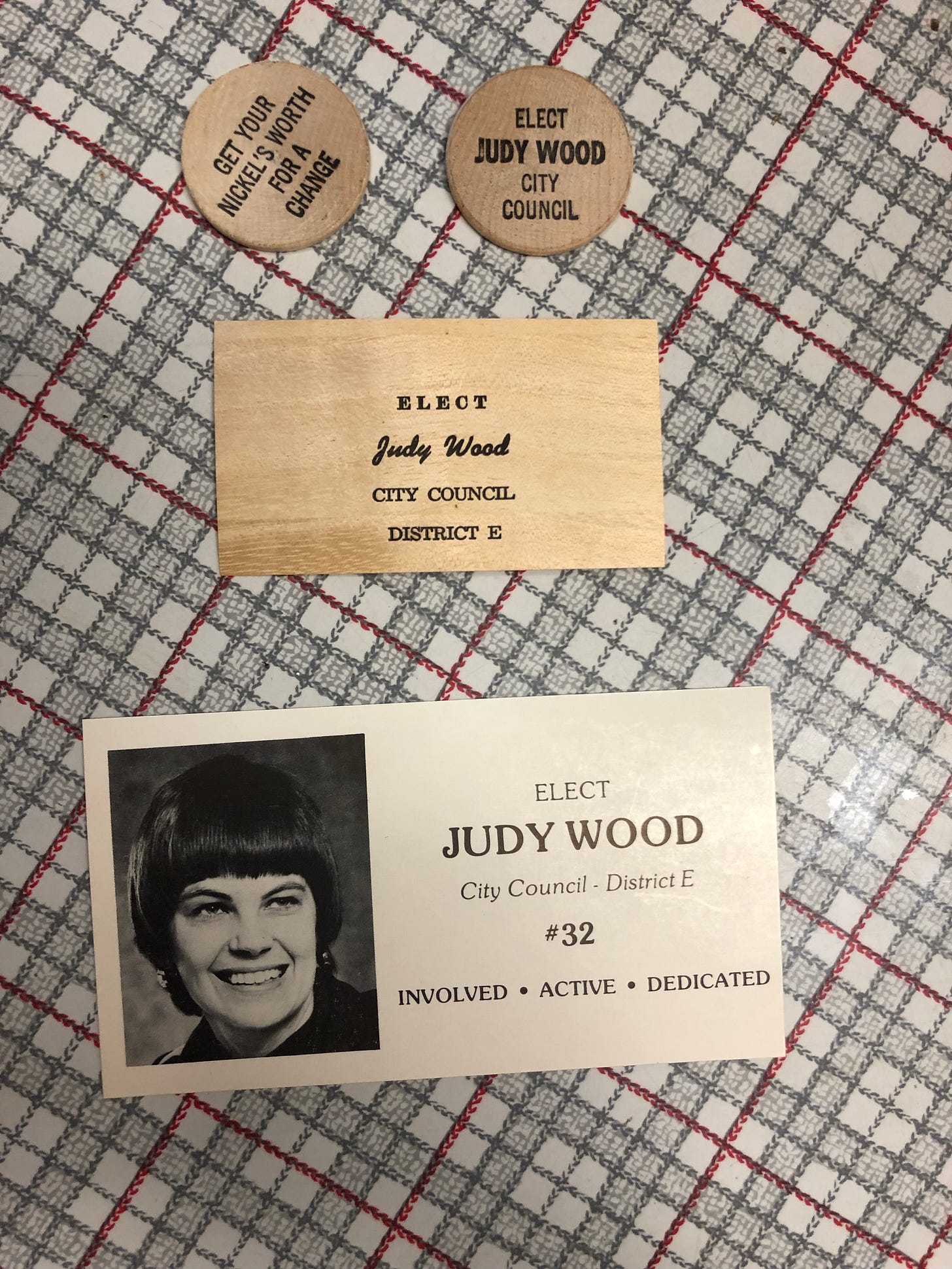

Like a lot of women who run for office the first time, Wood didn’t want to fundraise for her campaign. She assumed she would pay for it all by herself, but checks started arriving in the mail from friends and supporters. Her handwritten lists of expenses indicate that she spent her $446 in donations on a professional photo, ads, and lumber for yard signs. With hundreds of door hangers ready to disperse, Wood’s friends hit the streets with her. “We had a force of women,” she says proudly. “Every week, we hit that district with something. Door hangers, flyers, every Tuesday. We covered the district eight times, and I talked to every voter. I even gave out wooden nickels that said, ‘Get your nickel’s worth,’ playing on my name. They were flabbergasted,” she said of the four men she ran against. “They wondered what I would do the next day.”

It wasn’t just the local corruption she wanted to reform, it was also the dire state of the environment in Slidell, which had major flooding, contaminated water, sewer problems, and a lack of shade due to developers cutting down old growth trees for new houses. With a clever campaign slogan, her ads repeated the refrain that Wood was the one who would work harder than anyone else for the city and just get things done:

Who would work for more recreation facilities?

JUDY WOOD WOULD

Who would work to preserve Slidell’s green heritage?

JUDY WOOD WOULD

Who would study all the issues before voting?

JUDY WOULD WOOD

Who would give a fresh approach to city council?

JUDY WOOD WOULD

Who would work for recreation programs for all ages?

JUDY WOOD WOULD

Who would work for proper solid waste disposal?

JUDY WOOD WOULD

A concerned citizen who feels it is time for action – a clean green Slidell, recreation programs and facilities, and long range planned progress.

JUDY WOOD WOULD

Wood soon got a call from the head of Louisiana’s Republican party, asking to see her campaign plan. She didn’t have anything to send him, so she and a friend working on her campaign quickly wrote something up. He called back later and wanted to know where she had gone to campaign school and what other campaigns she had run. “Well, I ran campaigns for student council in high school,” she told him honestly. Republicans in Louisiana were so impressed with her, they asked her to help out with their campaigns for years.

For weeks, Wood and her campaigners had used a hand-drawn map of the neighborhood to mark which houses they had gone to and whose support she had. The other four men running, with the exception of the incumbent, Nunzio Giordano, barely campaigned. “A piece of limp spaghetti,” Wood described him, Giordano went around the neighborhood right before the election telling his constituents he just wanted to hold onto his job. “Well, the guys voted for him,” she says. “Their wives might not have, but he got enough votes to force the runoff.” One of the losing candidates in the district, Red Crockett, walked the neighborhood with her for the runoff campaign against Giordano, giving her an extra push. She won.

The other new Council Members included the first African American to serve on the City Council, Lionel Washington, from the city’s black neighborhood, and her activist friend, Jack Throop. Only one incumbent, Gerry Hinton, had won. Other new members included several small business owners, an attorney, and a social worker. They may have been new to the City Council, but they all weren’t reformers. Wood called them “the fellas.” They weren’t sure what to think of this woman who had just broken into their club.

The City Council and the press didn’t know how to address the first woman serving on the City Council since she was such a novelty. “Just call me Councilwoman,” she told them. Wood hit the ground running at the beginning of her term. She was the only member who didn’t have another job, so she was at City Hall all day. Constituents across the city started meeting with her instead of their Council Members simply because she was there, which allowed her to find out about all kinds of issues and concerns. The other Council Members soon came to rely on her to get things done and enforce the new anti-corruption sentiment. “They thought of me as a super secretary,” Wood says. “I mean, I wouldn't do their work for them. I made sure the minutes and the documents were right and made sure that if somebody said they were going to do stuff on a certain day, it got done. I made sure people did their job because we're paying city money, taxpayer money, to these people, and they were doing the city's work.” She was a stickler for showing up on time and doing the work.

Her first bill made good on one of her campaign promises. It was an ordinance to save trees, at least a few, on the property of each new house. The new city charter required the next City Council to write an ethics code. She took charge of it when she realized no one else on the Council was planning to work on it. First, she called a lawyer friend to get some advice. Then, she said, “I started messing around. Now, I'm not a lawyer, and I'm not that smart. But I just started putting stuff together,” explaining an approach that would serve her well over the next few years. Among other strict new requirements, the ethics code demanded a lengthy financial disclosure from each member, including all the properties owned as well as those of their family members. Wood explained the impact of the code over the years, which was largely enforced, “I don't think there's ever been a person in Slidell since then who's been indicted while they were sitting on the city government, meaning an elected official, or for anything that happened in my city.” Considering the corruption that would continue across Louisiana politics for decades, she considers it one of her proudest accomplishments of her term in office.

There would be only one term, and that was on purpose. A few months after the election, the police force asked for a raise. Wood opposed it on the grounds that the city should wait until the beginning of the next fiscal year to do it. After the vote, a reporter came up to her to ask why she wasn’t concerned about risking her reelection by going against the police. She told him, “I'm not running again.” She had only been in office half a year. The reporter wrote, “Judy Wood announces that she's a one-term.” But what she often repeated was, “I'm only here for one term. If I can't get my work done in four years, I don't need to do remedial.”

That freedom from the fear of losing reelection allowed her to always vote her conscience on every issue. “I didn't cut deals,” she said proudly. “You know, if you vote for this, I'll vote for something you want. And I said, ‘No, I don't keep bank accounts. I only vote on something if it's good. If I put up something that's not any good, don’t vote for it. But I'm not trading votes.’”

The local press had never seen anything like her. “There were five papers that covered us,” she explained. “Sometimes there were more reporters than people in the audience. There were just reporters all over, and that was really great, because it was an advantage for me. I had such a fantastic relationship with all of them. They trusted me, and I trusted them.” They could rely on her for a good quote, no matter what the topic was. Ciko of the Times-Picayune became a good friend over the years.

But those reporters also called Wood out sometimes as a newbie politician who didn’t quite know what she was doing yet. “Once in a while,” she admitted, “we came to tangle, but because they were right. I didn't know.” During her first year, she made a rookie mistake by not notifying the press when her subcommittee on the city budget met. Since there were only three members meeting instead of the usual five for a regular committee, she didn’t think it was necessary for the press to be there. “Well, they were furious at me, absolutely furious with me,” Wood said. “That's a sunshine law, and we had to notify them.”

Wood refused to tolerate the lazy work ethic and lackadaisical attitude of some of those employed by the city of Slidell. She was furious that the clerk for the City Council was working for local mortgage companies to look through tax records and report property assessments to them. She bluntly told the other Council Members, “If he's working part-time, well then, we only need to pay him part-time.” In the next budget, his salary was cut. When he resigned, Wood suggested that his secretary be appointed as the new clerk since she had been doing most of his job anyway. But, the other members pointed out, she didn’t have the necessary certifications. Wood fought back: “I just said, ‘No, she has done all the work. We're going to promote her. She can get her certification.’” The city paid for her certification classes.

One of Wood’s biggest political battles was getting the Council to vote for new federal funding for the Slidell’s sewers. To get the money, water meters would have to be installed at every home in the city. No one wanted to pay for it or pay more than their flat rate of six dollars per month for water and sewer. Wood knew it would take something dramatic to pass this bill and decided a play on words might get some attention, especially from the press. “It came time for the vote,” she said. “I needed five votes. I got up and placed a bullet in front of every Council Member and told them to ‘bite the bullet and do what was right.’ It passed eight to one.” Fighting for sewers was not glamorous, but it was absolutely crucial for a city built on a swamp.

Wood was true to her word about being an ethical Council Member, even if she lost friends or went against what the newcomers wanted. She explained the controversy over building a new bridge over a canal in the city: “If the old boys had still been there, it wouldn't have ever been built. But it wasn't safe because there was really only one major way to get from the north part of town to the central part of town, and that was Robert Boulevard. It was a mess. The people on the north part of town started asking to have that bridge built, and there was a real big brouhaha about it.” One of her friends lived right by the canal and was outraged that Wood would vote for the bridge. But it was a public safety measure, especially if there was ever an emergency evacuation for a hurricane. She had to be blunt with her friend: “I said, ‘Margaret, I have to vote for the bridge. It's what's best for the city. I am so sorry.’ Oh, she was mad at me for a long time.”

Wood’s career as a City Council member had been hard on her family. Her two children, who were in middle school at the time, had to answer the phone for her at home when she wasn’t there and take messages. People called at all hours to complain about everything from their garbage not being picked up to the flooding in the streets. They also refused to go to the grocery store with her because so many people approached her it felt like they were stuck there forever. “They were so happy when my term ended,” she laughed, “although they learned a lot.”

After her term on the City Council was over, Wood stayed active in Slidell politics for many years. While still serving on the City Council, she was been appointed to the St. Tammany Parish Library Board. It gave her an opportunity to implement many changes at the libraries, which had always been her main goal. Under her leadership, the Board fired a library director who secretly banned books he thought were inappropriate and lied about applying for a grant. Wood was thrilled when St. Tammany Parish’s Police Jury (essentially, a county council) finally approved the funds to build a new main library.

But the process to find the land to build it on became a mess. Eventually, Wood resigned in protest from the Library Board when the Police Jury voted to buy a more expensive piece of land that was not in the central part of the city. She knew it was a political favor to the property owner, and that was the last straw. Wood went to the Police Jury meeting about it. She said, “I handed a copy of my statement to every reporter. Larry Ciko asked me, ‘You're going to resign from the Library Board, aren't you?’ And I said, ‘Yes, tonight, at the Library Board meeting. This is my swan song.’ He had this reporter there from the Times-Picayune, and they were ready to take a picture and everything.” The next day the Ciko wrote that Wood had taken her gloves off. He quoted her at the meeting, “Volunteering should be fun. It shouldn’t hurt so much.”

Wood couldn’t go back to her old life as a housewife. By then, she was divorced. Her kids were grown, and she could move anyplace she wanted. Instead, she chose to stay in Slidell and run a brand-new maternal and child health clinic at the city’s hospital. She looked back on this time fondly: “There were several things that opened up for me as a single woman. I had so many connections by that time.”

When the CEO of the hospital had trouble getting the state to match a federal grant for the clinic, he knew Wood could take care of it. “Let her do what she’s probably good at,” he said about her. She went over to her old friend and fellow Council Member Gerry Hinton’s office. She had been critical of his ethics many times, but at the end of the day, they were still friends. He was now in the state legislature and would be able to help them get the grant. Wood said, “I went in, and I said, ‘Gerry, I gotta have that money. It's for this clinic. It’s for the women. It's for people in your district, and the state's not doing it.’” She pleaded with him until he agreed. “Right there in that office, he made a phone call. He told me to drive up to Baton Rouge the next day to pick up that $600,000 check.” It was the largest check she had ever seen, and she guarded it with her life on the way back to the hospital.

Despite all the opposition she had faced from “the fellas,” when she had been in office, they came back to Wood whenever there was a leadership vacuum in Slidell. She told one story about when they took her out to lunch to ask her to run for parish assessor when she had no experience in that area. “I said, ‘I bet. You don't want somebody honest.” She knew that they were still doing underhanded property deals. There was no way she would run for office again anyway. It was still a very conservative parish in the early 1990s. The fellas wouldn’t give up, though. Later, they asked her to run for mayor. She was living outside the city limits at that point and could have moved back to run if she had wanted. If she had done so, she would have served during Hurricane Katrina. She cringed to think about it, considering the severe destruction and the long-delayed recovery in Slidell.

By that time, Wood had retired and had moved to Lacombe, west of Slidell, with her new husband, Adrian Barton, an oil field service engineer she had met through volunteering as a jazz DJ at the WWOZ radio station. Her radio show became so popular that DJ Davis McAlary (played by Steve Zahn) “sat in” for her during an episode of the TV show Treme. Barton and Wood were at their home when Katrina hit. They survived, but their roof did not. It took them months to get the power back on, but they knew they were lucky that their home didn’t flood.

In 2016, Wood and Barton made the decision to move to Tucson to live near Wood’s daughter Marcy, an education professor at the University of Arizona. The first thing she did was join the League of Women Voters. Members were so impressed they asked her to be president just a few months later. She ran the league’s office, started the popular Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion committee, and continues to mentor dozens of women who want to “just do something” about the state of local and federal government. She’s a registered Democrat now, a political switch she knew she would make long ago as soon as her father died. At 83 years old, she is still a force of nature, emailing her committees with new ideas at five in the morning. She jokes that her mother always said she came out of the womb ready to organize.

The word “organize” in a political sense can be pretty vague. I get the sense that Wood knows it’s more than just hosting meetings and setting goals to make a change. Successful organizers have shown that it has to include building a sense of community and making everyone feel included, valued, and appreciated. She sends thank you letters and birthday cards, makes personal phone calls, and ensures that events are well-planned down to the last detail, including the snacks and coffee. This is the kind of grunt work that makes ordinary people stick with an organization and feel motivated to do the work.

I ask her a few more questions before I left as we tidied up the mess we created on her dining room table looking through her box. I’m curious about what impact a “newcomer” can really have on politics in the South. “Do you think people who move to the South can ever really belong?” I asked her.

“Oh, I belonged,” she says confidently. “I was really accepted. I was accepted because I did so much blooming work. I think to live in New Orleans, you have to embrace the culture. And if you can't embrace it, then you need to leave. I had an opportunity to really have an impact on it.”

“Did you feel like you were a Southerner?” I asked. After all, she lived in Louisiana for 43 years.

“No, I never felt like a Southerner,” she admitted. At heart, she is and always will be a Midwesterner with a strong work ethic and an obsession with doing things by the book. But that doesn’t mean the fellas and everyone else in Slidell didn’t appreciate all the positive changes that she made in their government and in their daily lives. “What they really knew,” she said, “is that if I said something, they could trust me.” And that’s the only way—whether led by a newcomer or old timer—a political transformation can happen.

Wood’s path to political activism and winning an election is similar to that of a lot of other women. Many first get involved in organizing by advocating for their children, whether in PTA or neighborhood groups fighting for better schools, daycare, parks, libraries, or health care. This unpaid volunteering, which was often done by women who were not working full-time in the past and working women today who are desperately squeezed for time, may not be a “real job,” but these efforts are how political skills are honed and networks are made. They can also launch women into new political careers, not just running for office, but it many other roles.

I’m guessing today that there are many, many women across the country who are livid about rampant corruption or just terrible policy in their local, state, or federal government. Since the 1970s, women have run for office in waves during backlashes to their rights. 1992 was called the “Year of the Woman” when several women won U.S. Senate seats. In 2019, the squad and many other Democratic women helped win back the House. Mark my words, there will be another wave of them running for office soon. Wood’s success should be seen as a model for them. After all, if Judy Wood would, I’m sure that many other women could, too.

Very interesting! What an inspiration. I’m glad you got her whole story.

What a fabulous read about this amazing woman. How fortunate you are to know her!