In this inaugural episode, my niece Hadley and I interview my mom about her early life in Liberty, Missouri, being a preacher’s kid, the integration of public schools in Liberty, the death of her mother from cancer, the hijinks of her teenage friends, “The Rejects,” and going off to college at Oklahoma Baptist University.

Kate: Hey! Today is December 29th, 2024, and I'm here with my mom and my niece, Hadley. I wanted to welcome you both to the very first episode of my podcast. Thank you for being here.

Hadley: Thank you for having us.

Mom: Yeah. Thank you, honey, for inviting us.

Kate: You're welcome.

Kate: I think we have a whole lot to talk about, and Hadley and I have a lot to listen to, all of your stories. So, we're going to start at the very beginning of when you were born in 1949. You were born in Excelsior Springs, Missouri, right?

Mom: Yeah. Missourah, we say back in the Midwest.

Kate: Missourah, sorry. I did that wrong. And when did you move to Liberty?

Mom: I was just almost a year old. I looked myself up in the 1950 census and found out I was still living in Excelsior Springs. So, sometime during my first year after the census was taken, we moved to Liberty. My dad had been a minister there at a small, well, at the first Baptist Church and my mom, dad, and my older brother and sister lived in a parsonage right next door to the church. They have a lot of memories. My sister has a lot of storiess of being in the parsonage, which was an old two-story, kind of rambling house, but I have no memories of that, of course.

Hadley: What's a parsonage?

Mom: A parsonage is a house that's owned by the church and the families, the minister's family, can live there free. It was always kind of the way the church supported the minister without a big salary, but it always became a problem because ministers back in those days would go their whole lives and never have owned a home. So then, when they were too old to have a church anymore, then they were kind of out on a limb. So, that's something that changed during my lifetime, that churches started paying ministers more, and they were able to buy their own homes.

Kate: That's interesting. Where were your parents from?

Mom: Oh, my father was from Wichita. Well, the outside of Wichita. Little area of farming community in Kansas but moved into Wichita during the Depression when my grandfather had to give up the farm and he became a post delivery guy, postman. And my mother grew up in Henryetta, Oklahoma, a small town that was south of Tulsa, about an hour's drive south of Tulsa. And they met in college.

Kate: Where did they go to college?

Mom: Well, they both attended college at Oklahoma Baptist University in Shawnee, Oklahoma.

Kate: That's pretty unusual at the time, right? To go to college in the, they were there in the--

Mom: I’m being recorded.

Kate: That was my stepdad!

Mom: Yeah, yeah, that was very unusual.

Kate: That was in the ‘30s that they went to college?

Mom: Yes.

Kate: In the Depression?

Mom: Yes, yeah, it was unusual. I'm sure. My dad first went to college in Emporia. No, Ottawa, Kansas, and he went there first for, I think, a year or more, and then he dropped out and worked to gain or to earn money to then, because his goal, I think, was to go to Oklahoma Baptist University. It was kind of an up-and-coming college back then, and a very pretty school, also, very pretty school. Pretty, pretty brick buildings, and, my grandmother--

Kate: Oh, what was your mother like?

Mom: Well, she was a musician from when she was very young. She was driven, I think, to it because it wasn't that her parents were. So, it was something that I don't know genetically where it came from, but I think it did, because your little brother Austin was kind of the same way. And, she had a small baby grand piano. She took lessons there in Henryetta as a pianist and accompanist, and I know she played for the Rotary there. That little bust that I have in on our piano came from them.

Kate: Oh, yeah.

Mom: The Rotary gave her that when she went off to college, and she played at a lot of weddings. And she also sang, and I remember one time my grandmother telling me how it broke her heart that my mother would get up so early in the morning to practice before she went to school, and there was no heat in the house early in the morning, and she would be playing the piano in her winter coat with gloves that she had cut the fingertips out of so she could feel the keys.

Kate: Wow.

Mom: So, that was devotion.

Kate: Did she? I remember, did she want to go to Juilliard, or something?

Mom: Well, she got a--

Kate: What was the story?

Mom: When she graduated, she was offered a scholarship to an Eastman school of music.

Kate: Oh, Eastman. Okay.

Mom: And my father at the time really, he wanted to marry her. And he was really worried he might lose her if she took that scholarship, and my sister often thinks back to that. She thinks of my mother having to make that decision.

Kate: So that was after, already after she was in college, and they had met.

Mom: Well, she was a senior probably when that hit, was probably like going to graduate school. Instead of having her go off to pursue that, and it would have been in piano performance that she did that.

Kate: Yeah.

Mom: I mean could have done that. But she made the decision. I know that he wanted to start seminary up in Kansas City, Kansas, Kansas Central Baptist Theological Seminary, and he drove her up there to look at the seminary and see Kansas City. He also, he entered a contest he would have been a senior in college and there he found out about a contest. I think the contest was sponsored by the Oklahoma Baptist Convention. That's how we would call it. It was statewide, and it was for writing an essay about some history of the Baptists in Oklahoma, writing a paper about that. But there was a money prize associated with it, and he really wanted that money to buy her a ring. So, he worked really hard on that. I think he spent most of the summer working on it, because I know he traveled around Oklahoma, and he did interviews in different churches. There was a women's group called the Women's Missionary Union. They called it WMU. And he went around to those churches and interviewed the women that were involved in that program to kind of get a history of that program in Oklahoma. And he wrote his paper on that, and he won the contest, he got the money, and he was able to buy her an engagement ring. And he was hoping that would change her mind to have that ring, and apparently, it did. It almost sounded to me when I was growing up like a story from the Waltons, or something.

Kate: Right, yeah.

Mom: A TV show.

Kate: So, what were your, you had an older brother and older sister. What were they like?

Mom: Well, they were quite a bit older than me. They were 13 months apart, and they were 7 and 8. My sister was turning 7. My brother had just turned 8, or turned 8 the month after I was born, so I didn't really. I don't have memories of them as children. And

I always thought I had always grown up, kind of thinking I was like an accident. The the accidental kid that showed up, and then I found out I was much older. My dad told me that that wasn't true, that he had started his master's, but hadn't finished it, and he really wanted another child, and my mother had said, “Well, if you finish your master's we can have another one.” And so, he did. He finished in this in the summer end of the summer semester, I guess, in ‘49, and then I came in October, so he always told me that I was his graduation gift.

Kate: Like, the reward!

Mom: Yes, the reward for finishing.

Kate: Another kid!

Mom: And I imagine he had probably started it, and then just let it drag on because he was busy trying to support a family. But I always thought that, that really made me feel so much better when I learned that story. I don't really know.

Kate: You were wanted, yes!

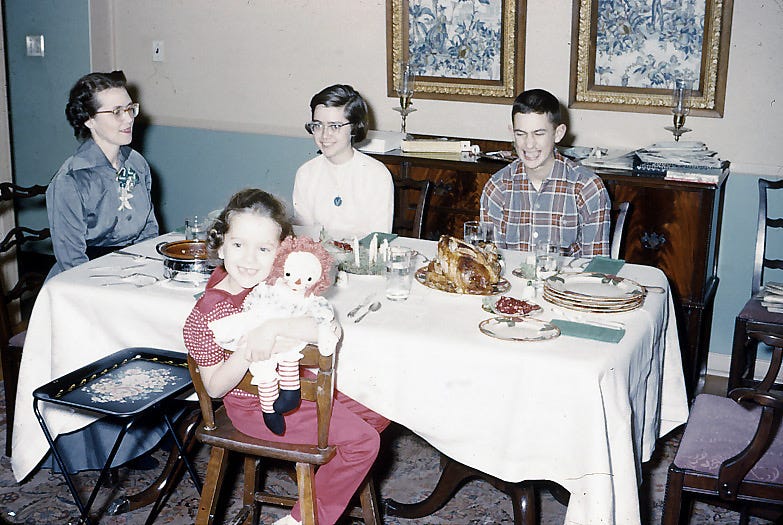

Mom: Yes, but I always I did feel like I was observing another family rather than being a part of it, because the four of them, you know, especially my brother and sister, were always so close. You know, there are pictures of them, and they were little. They had cowboy outfits alike, and they slept in a room with bunk beds. When they were little, they had chicken pox alike. They played with the same kids.

Kate: So you were. You were observing your family.

Mom: I felt like.

Kate: As the youngest, yeah.

Mom: Yes, yes, but I observed everything, that they all seemed to make the plans and know what was going on, and I was the last to learn what was happening, or where we were going, or even why we were, why we were doing something, you know, and so I just, I felt like an observer as a young kid, not so much a participant.

Kate: And your dad was in World War II right?

Mom: Well, he was.

Kate: He was a chaplain.

Mom: Yeah, he was in the Army Air Corps, and he served as a chaplain in South Carolina. I guess there was a base there, so mostly.

Kate: So, he was gone? When your siblings were younger, or is that right?

Mom: Well, when we he moved out there when he moved out there, they he was at that time he was at a church way out in eastern, I mean western Kansas.

Kate: Yeah.

Mom: Russell, Kansas, I think, was where he was living in, and so he went to the base, and when that happened, my mother went back to Henryetta with her two kids.

Kate: Okay, to stay there.

Mom: Yeah, for a little while until he got base housing, and then they moved out to South Carolina, and they lived there for a while, and I remember seeing an album when I was young, that had black and white photos of the base, and of my sister and brother on the base. It looked like that they maybe went to sort of a nursery school there, and aso they lived there for a little bit, you know.

Kate: Remember, we had that weird little organ in the basement that was like--

Mom: Yes, that was the pump organ.

Kate: Used by a chaplain or something.

Mom: Yes, that was.

Kate: Like a portable organ.

Mom: Yes, that was like a called a field organ. Yeah, because he had to be out in the, you know. He was always there at the base, but they probably, I know my sister. We have a picture of him where he was in his uniform. He's on a hillside, and you can see the troops are sitting on the hillside, and he's looking. They're sitting on the hillside. He's at, toward the bottom of the hill, and you can see that pump organ behind him. So--

Kate: It‘s right there?

Mom: Yeah. So, somebody was, you know. Somehow, he did outdoor services, and my sister said he did several services throughout the day on Sundays for troops from different backgrounds, different religions. And just recently we were talking kind of about him, and she had this story she told me that he black troops and the white troops didn't attend the services, I guess, at the same time, and that, but that an officer brought a group of black serviceman to him and wanted him to do a service for them, but he was wanted it to be kind of as a punishment, because these guys had been out late and had been drinking the night before, and so he was kind of forcing them to do this, and my father got very upset with the officer, and said, he said, “My services are never to be used as a punishment. I don't, this is never to happen again.” and he wanted to integrate the services. I remember hearing that too.

Kate: Yeah. So, you moved to Liberty when you were one. Can you talk about what Liberty was like since you spent your whole childhood after that there.

Mom: I did. I did. Yeah. Liberty is a little town north, kind of northeast of Kansas City. When I grew up it was very separate from Kansas City. Right now, now that the two, all the suburbs have just blended together, you wouldn't know when you ever crossed a city boundary. But it was very separate, and we referred to Kansas City as “the city” we always like. We're going to the city, and it was like a big trip. We got dressed up, we wore dresses and our little coats with gloves whenever we went to the city, had on our Mary Jane shoes. Occasionally, we might ride the bus with my mother to go in if she was shopping for something, but I remember mostly my dad would drive us. My mother did not want to drive in the city, so mostly my dad would drive us.

But I loved Kansas City when I was little it was very exciting to go there. Liberty seemed to me it was such a little tiny town, almost like a town out of the 1930s movie is kind of in my mind how I remember it, because it was a pre-civil war town. It had a courthouse on a square, with all the shops around the courthouse, and that was where we shopped. But it was a very, very segregated and very Southern town, and [15:00] black families didn't shop in in our stores or around the square. I've heard stories about if they needed to use a drugstore they'd have to go to the back of the drugstore, and somebody would come there to wait on them. And it wasn't until I was in 4th grade that the town fully integrated the schools.

Kate: Yeah.

Mom: And I was trying to figure. I think it was probably around 1956, ‘57, maybe ‘56 when that happened. And at first, there was a small school in the in the black part of town that probably held all the grades, and then at some point, the high school kids

that could go to high school attended a school in Kansas City. They weren't allowed to attend the high school.

Kate: They had to go all the way there.

Mom: So, I'm guessing maybe someone in the in the community drove them. There wouldn't have been a bus they would have gone on. And then that the High school was integrated first, and then gradually it filtered down, and the grade school was left till last. And so that happened during my 4th grade year. And that was kind of a pivotal year in my life growing up, because the way it worked was the way our school handled it, our district handled it was they sent all the 4th graders to the school that was in the black part of town that had been Garrison School, and I thought I was going to another town. I had never been in that area. I didn't really know where it was. It seemed so far away. And now, as an adult, I realize that I can stand on the square and look two blocks and see that school. But as a child. I guess I just was unaware of that, and I and I had to ride a school bus. That was my first experience riding a school bus

But it turned out to be the best year I had, I think, especially in my elementary through middle school. That was my favorite year because the 4th graders were isolated from the big kids and the little kids. You didn't have to worry about being bullied by the big kids, and it was an adventure to ride the bus there, and it was an adventure to be in this whole new part of town, different houses, different families. There were chickens. I remember some of the houses around our school hearing the chickens and seeing the chickens out in the yard, and there were no chickens in any other part of Liberty that I had been in.

Just things like that. And we didn't have cafeteria in the school. We had to ride a bus over to the, it was called the middle school, but it'd be like the intermediate school, you know, to have a hot lunch. If you did that you missed your recess. So, most kids didn't do that, and since we didn't have a cafeteria with chairs in it, we had our lunch on the floor of the gymnasium. We would walk to the gymnasium, take our shoes off, line our shoes up, and pick up a big sheet of newspaper, big double wide sheet of newspaper, and lay that out on the floor and eat like a picnic. Then you'd gather up your newspaper and throw it away, you know, or get rid of it before you went out to recess.

And I remember that year, I loved my 4th grade teacher. And I remember she read Tom Sawyer to us that year. I can remember being on the playground, hot and sweaty and ready to go in after noon recess and saying to everybody else, “We can't wait to go in, because we get to hear Tom Sawyer.” You know, to hear another chapter of it.

Kate: Yeah.

Mom: Yeah, that was very pivotal to me that she read aloud to us. And that's really about the only teacher. I'm sure there were other teachers that read aloud to us, but maybe because it was the story of Tom Sawyer and Becky Thatcher and Huck.

Kate: It’s about Missourah.

Mom: And it was about Missourah. And then we took you kids there when you were little to see where Tom would look out his window and hear the catcall from Huck. Time to get up and go outside and have an adventure. Liberty was very segregated.

Kate: It was.

Mom: Watching that that change. I really lived through the late fifties, early sixties of watching how that town changed, and the kind of as an aside. My sister and I, older sister and I went back to Liberty. I think we were back there for a reunion, or to visit family or something, and went down to the archives to look through our old newspapers. Our old town newspaper from that time. I wanted to see if there were any articles that were written about this integration of the lower grades. I do know that when that happened, the teachers who'd been teaching at the black school were not allowed to teach at the white school.

Kate: Yeah.

Mom: And I thought, well, were there articles, letters to the editor? I knew that there were a few kids in my class that didn't show up in 4th grade. Their parents sent them somewhere else, so I knew that was controversial as looking back on it, and I even knew at the time that we were doing, I felt like we were doing something kind of unusual that was happening in our town, and I was getting to be a part of that. But we looked all through the papers and could never find anything and while we were on that visit I was so surprised, but while we were on that visit, we had lunch with some friends that were longtime Liberty people that had stayed there. One of them was a teacher in the school, and we mentioned this, that we hadn't seen the articles, and she said, “No,” she said, “and that's why it went so smoothly in Liberty, because the paper--

Kate: They didn't want to talk about it, expose it too much.

Mom: They just they didn't want to give it space.

Kate: Yeah.

Mom: Yeah, they didn't give it space. It was kind of like, we don't give it oxygen.

Kate: That makes sense, yeah.

Mom: Though I'm, you know it was talked about. It just wasn't recorded. Yeah.

Kate: Hmm!

Hadley: Do you, I don't know. I can't do the math in my head but your siblings. How old were they when you were in 4th grade? And do you remember, like them going to school if they integrated before you?

Mom: Yeah, they did they, the high school was integrated first. So, when they went through high school, it may have been about the time that they went through that it was integrated. And I know, I think, a year close to my main. Well, they were back-to-back in school, and I don't know what year this happened, but the, there was a black girl. Let's see. I can't think of her first name. Her last name was Slaughter, because our, China Slaughter, was her father, who was the janitor at my grade school. And she was either I don't know if she was valedictorian or voted something in her school, in the high school. It was like a very unusual honor, you know, not an unusual honor, but it was unusual that that this honor was given to her. It was really a cool thing to have happen. And I remember China very well, because he was the crossing guard at our school, but he also, because my mother taught music there, and she pushed a piano. She would have to take the piano from room to room. There wasn't one music room, so she would be the teacher who would come into the room, and while the other teacher would go out, I guess, and have planning time. China would help her push the piano from room to room. It was on a big set of rollers. So I felt like I knew him. I felt like he was a friend of mine personally, because he knew my mother.

Kate: Yeah.

Mom: Yeah, I don't remember there being any issue ever talked about in in our home, you know, related to the integration. I just remember how I was afraid to go because it was a school I'd never seen or been to, and it wasn't a thing that my mother talked with me about. It was a thing my father did. I remember him sitting on my bed and prepping me for getting ready to go. And, how my same friends would be there and new friends to sort of talk.

Kate: So, your dad at that time, he wasn't exactly a minister, right? He was working for the association.

Mom: Yeah, he had a different role when he came to Liberty. It was called Associational Minister for two counties, Clay County and Platte County, and he had that job the whole rest of his life till he retired, which he retired the year you were born. So, from the late, early fifties, you know, like 1950 ‘til about 1978 is when he retired. He had that job. So, his job was to help establish new churches and support all churches that were already, and you know, going. And you know, he ran training sessions for them, and he ran a camp. There was a camp grounds that were donated. So, that camp he helped build that camp up and was always kind of in charge of that camp. That was a big part of our summers was his dealing with all the issues and the creek flooding,and stuff up at the camp and building new buildings.

Kate: What was the name of that camp?

Mom: New Hope. It doesn't exist anymore. The grounds were sold, but it was there for a number of years, a lot of years.

Kate: What was it like, I know you and your brother and sister refer to yourselves as preacher kids.

Mom: Yeah.

Kate: Whatever that term is. What was that like?

Mom: I think my sister thrived under it. She was the good child. My brother hated it. He just despised it, and so he really kind of acted out and rebelled against that when he was going through high school, and I was kind of middle of the road. I rebelled, but never openly, you know. I participated in all the church things that he expected us to, and that we did.

But our mother, it kind of shifted after she passed away, because she was, she really drove it. She was very active in our church. My father was not active in the church we grew up in because on Sundays he was always working in another church. He was filling in for somebody or helping take part in maybe a ceremony that might be going on if somebody was being ordained, or something like that, or he did fill in, reaching in. So, it was not very often that he was actually with us on Sundays. It was a thing that my mother orchestrated and had us all involved in.

Kate: Yeah. I've just always been amazed. You have all these Bible verses memorized and hymns and stuff, and can just rattle them off.

Mom: Well, that was a part of my.

Kate: Not really what we did too much, but.

Mom: Well, it's true, I mean you all were confirmed. But we switched churches by then, you know, and the Presbyterian church, a little more liberal and just so you know, and your dad had always said he really wanted that a part of your education, too. He wanted that a part of your childhood experience. He made the decision for us to go to join a church and to take you guys to it when you were younger. It was a thing that we discussed and consciously decided that you needed to have in your background. And it makes a difference when you're reading and you're older.

In fact. Nick told me, because your older brother told me when he did his semester abroad in college, and he was doing art history in Florence, I believe he was. He said he felt the difference between the other students he was with who could look at a painting and knew exactly what the story was about and who the characters were depicted in the story that was depicted. And he didn't know.

Kate: Right. Oh, he didn’t? That’s right, he wasn’t paying attention too much. That's right.

Mom: Well, he went through confirmation, and then he then he took. He's, you know he would. He said that was it for him and so he didn't go. You know he didn't grow up, and it wasn't the way your education in the Presbyterian Church was very different than what ours had been in the Baptist Church. You know, we were learning Bible verses every week, and being drilled on them and such like that. That it was just a part of what you did there. The culture.

Kate: Yeah. You spend a lot of time, I know, like your summers going to Henryetta and being with your cousins and aunts and uncles and grandmother, grandfather. What was all that like down there? That was like a whole other world there.

Mom: Oh, it was. To me it was just, you know, I'd never been to Disneyland, but I knew that Henryetta was better than Disneyland when I was growing up. We knew, yeah. When I was little, we always went with my mother. Well, we had the holidays there. That was the family events where when we drove in the car, and we’d go down and stay at grandmother's for holidays.

But the special times really were in the summer. We always tried to go right when school was out, hopefully the end of May. If school was out early, very, very, first to June because of the heat. It was just unbearably hot, just that much further south than us, and we took the train. We took a train called the Katy train. I have to think. It was like KTA. The Kansas, Topeka, and Atchison, something like that. Maybe Kansas City, Topeka, and Atchison. But anyway, we would take that train from Union Station, and it was not air-conditioned. So, the windows were down, and dust was blowing, and we had a little shoebox with our sandwiches in it. There was a little man that would sit at the back of the car that was like the, I don’t know what you would have called him, was like the guy that took the tickets, the ticket taker, but he also had a box of candy back there that would be melty, like candy bars, and I remember my sister and I would only get Paydays because they didn't have chocolate that would melt all over you. That was my first introduction to Payday candy bars was on the Katy train.

My grandmother would pick us up in Checotah, a little town where the train stopped the closest stop that it had to Henryetta and her big black Cadillac, and then later, her big Lincoln cars. That first air-conditioned car I think I'd ever ridden in was hers. But and then we go back to Henryetta, and Henryetta was where my grandparents lived, my great uncle and his family of kids, and my great aunt. And they all were involved in businesses within the little town of Henryetta, and my grandmother's big, she had a big Dutch barn house. It had four bedrooms in it, and two-story, big corner lot. She was always working in her yard because it because she lived on the corner lot. She thought it was so important that her yard look nice, because you could see it from every side.

Kate: That’s funny.

Mom: And so she worked in that yard early every morning.

Kate: I love her name. Her name was Willie Pearl.

Mom: Right.

Kate: And one of my nieces is Willa Pearl.

Mom: That's right. I know.

Kate: I love that she was named for her.

Mom: I did, too. I was just take so struck. Take learned that, you know. Yeah.

Kate: And she was from Texas, right?

Mom: Yes.

Kate: She was this very small, like scrappy kind of Texas woman who always made bacon every morning.

Mom: Oh, so scrappy, Texas. Every morning. Yeah, every morning. There's always a can of bacon grease on her. And she made gravy for her dog, for the dogs, dog food every night. She always had a little pan of gravy.

Kate: Like bacon gravy?

Mom: Bacon gravy. That's how you used it.

Kate: What was the name of her dog?

Mom: Tippy.

Kate: Oh yeah, Tippy, okay.

Mom: Yeah. Tippy.

Hadley: This is your great aunt?

Kate: No, her grandmother.

Mom: This is Grandma, Grandma Boerstler.

Hadley: Oh, your grandma.

Kate: Her mother's mother.

Mom: Yeah. Willie. Willie Pearl. Farmer was her last name. But yeah, and my grandfather owned a grocery wholesale house there with his brother. My grandfather ran the wholesale part of it, and his brother, my great-uncle, ran the business office, which was air-conditioned. It was a separate little office built onto the big old, kind of sandstone is how I remember.

Kate: It's right by the train tracks.

Mom: Yeah, right by the train tracks, because the train cars would pull up and kind of pull off the track a little sidetrack to pull up right next to the building where they would load and unload groceries, and my uncle, both my uncles, both his sons, worked as salesmen, until one of the uncles kind of branched off and made his own separate wholesale house out in Bristow, Oklahoma, and my other uncle, at one point inherited the family lumber yard, and the went off and took care of the lumber yard. But my cousins worked in the wholesale house in the summers from when they were ten or younger than ten.

Kate: Yeah.

Mom: And I did, too, and I would go down there. My granddad always put us to work. That was a part of--

Kate: Being there?

Mom: Oh, yes, and it was just expected, you know, that that you helped out, and of any kind of family business, you are a part of it. And so, I would stamp tobacco, which I was in a little bit cooler room because the tobacco is kept in the cooler spot, but I'd have to open those cartons of cigarettes and float the stamps in a little dish of water, because they kind of work like decals and have to put them on the bottoms of the cigarette packs. And that was how they paid the tax. I didn't realize when I was first doing it that it was tax money. I just thought they were pretty decals and found out from my grandfather right away.

Kate: You thought you were just doing it for fun! For decoration.

Mom: I did, I found out right away that it was. You had to be careful and not waste those. It was money. It was worth money. And at first, I wasn't very good at it, and my stamps would float around in the water and lose their glue. And oh boy, did I get in trouble for that! Because that was wasting money.

But I just loved that part of my life because my grandmother would have us run errands for her. And at home, you know, it was my older sister and brother that were asked to do things. I was just kind of still, as I said, an observer of what was going on. But when I was at grandmother's, I was very involved, and helping her with different things around the house. She always was painting something. When I say painting, I mean, like furniture. It was like, open a can of paint, and you slap the paint on. She would have us work in the yard and pay bills for her. She'd have us run uptown with the check to pay because any store in town you could run a line of credit, and all I had to say when we were, especially when I got older, and after my mother had died, I did a lot with her where I'd be down there longer in the summers.

They had just changed the streets from being pull-in parking to being parallel parking, and for my grandmother she took such umbrage to that. It was almost like the town had done it just to thwart her because she could not parallel park her big old Lincolns that she drove, and so she would drop me off in front of a store with the check, and I would run in to pay her bill while she circled the block and come back and pick me up, and I can remember when I'd run in.

Kate: Didn’t they live like a few blocks away from that area?

Mom: What's that?

Kate: Didn't they only live like a few blocks away?

Mom: Oh, they did live a few blocks away. Yes, but she didn't walk uptown.

Kate: Oh. She Nnever walked over there?

Mom: Well, it wasn't like, people didn't exercise the way you think about it now, and for her, having a car was a status symbol. And it would be people who couldn't afford a car were the people that would walk downtown.

Kate: Yeah, okay, I see.

Mom: So, so much of what I learned growing up in Missouri and Oklahoma. A lot of it was so tied to status. And how you presented yourself. That was very important, so she would drive the car up, I'd hop out, but when I take it in, and I'd say, “This is for Ms. Boerstler.”

They'd say, “Oh, are you Ms. Boerstler's granddaughter?”

I'd say, “Yes.”

“Well, which one are you?”

And then I could say, “Well, I'm Anna Vena’s youngest.”

“Oh, I just loved your mother,” they'd say, and that would happen store after store after store, you know. I loved that feeling of belonging.

Kate; They knew who you were.

Mom: There was a place where they knew who I was, that because they knew who my family was, and I loved that feeling whenever I was in Henryetta. It always felt like home.

Kate: Yeah, and you had your cousins were closer to your age, right?

Mom: Yeah, I had two. I had four cousins in that family when I, in my uncle's family, and they lived right across the alley from my grandmother. So that was just wonderful to be able to run back and forth across the alley to me. That was kind of magical to be able to have family that close. And we'd spend the night with them, or they'd spend the night at grandma's, and I mean we'd be running around in the dark playing flashlight tag, or you know, in the in her big yard. The grownups might be out sitting under the trees in her lawn chairs. She had those metal lawn chairs that you could kind of rock in a little bit, and our job would be to be watering. We'd have that long hose, and we'd drag it from flower bed to flower bed and water while the grown-ups sat and talk in the shade.

Kate: And I know your cousins, was it Benny and Jimmy?

Mom: Yes.

Kate: Always like to play pranks, right?

Mom: Oh, they did!

Kate: Like wild boys.

Mom: They were the wild boys of summer.

Kate: Up to no good.

Mom: Up to no good. They always had gadgets, were inventing things. They both, they had the subscription to Boys’ Life, and there was always things in the back of Boys’ Life.

Kate: Oh, about how to build stuff?

Mom: Yes, how to build stuff or make things. And I remember one of my, one year when I got down there, they had made a harness and a parachute that they put on the cat, t throwing the cat off the roof of the house to see if the parachute would work. They had a wonderful--

Kate: Didn’t they have a zipline or something in the backyard?

Mom: Well, it wasn't exactly, yeah. We called it a monkey bridge. They had a tree house in a huge, tall, tall tree that just towered over their yard, and it was so tall it had a straight. It was very hard for me to get up there, because it was just a straight rope ladder that you had to get up, climb up to get there. So, once you got up to the top, you wanted to stay. But it was screened in, and it had the back seat of an old car was up there to be like a kind of like a little sofa or a seat to sit on up in the treehouse. And my uncle made a little box that would go up and down on a pulley that ran on an old lawnmower motor. So, it was a motorized pulley that this box could go up and down that you could put things in, you know, like supplies or tools, or magazines, or books, or lunches, or you know, the cat could go up and down in this little motorized elevator.

And then from that tree house to the corner of the yard, they had a, we called it a monkey ladder, but it was something that my uncle had learned to build when he was stationed in the Philippines during the wars during World War II, and they would use it. It was like three ropes that were you could walk on one rope, and you held on to the other two ropes as you walked. They would be like the points of a triangle, and then they wove another rope in between the sides and the rope that you walked on to sort of catch you if you fell, but it swayed back and forth. And the boys could just run across that rope. It was so scary to me, but they’d just run across it like lickety split, and they had the coolest backyard because of those things.

They had a big old metal barrel that my uncle had fastened to two ends of like a saw horse, and they had an old saddle over that barrel, so it was like a horse. You could get up on the saddle over this barrel like you were riding a horse, and you all actually had one of those when you were real little, because when we moved to Stillwater he brought one. Yeah, he brought one up to you all, and it was a real small saddle. He said it was a mule saddle that he had traded, done some trade for to get that mule saddle. I couldn't believe when he showed up with that, either, because it was such a deja vu for me.

Kate: It was awesome.

Mom: There was always so much activity going on over there.

Kate: Yeah. Well, why don't we talk about when your mother got sick and passed away when you were pretty young.

Mom: Yeah, I was. I think she, well, she got cancer. And I, as I look back, the timeline, pivotal was that she, it was breast cancer, and she had an operation. She had a mastectomy when I was in 4th grade, but I know that she had a lump, and our family doctor was watching it for a while, you know, so I think that she really became sick with it when I was in 3rd grade. And then, the operation happened when I was in 4th grade.

Kate: Did that happen in New York? Was that when you went there? Or was that later?

Mom: No, this was in Kansas City or in that Kansas City area where that occurred. I remember, when she was in the hospital, I was too young to visit. y\You had to be. Maybe you had to be ten or older, and I wasn't ten yet, or maybe you had to be twelve. I'm not sure what the age was, but you had to be a certain age before you could enter into the, back where the rooms were in the hospital, so I would have to stay in the waiting room. I remember sitting in there with a stack of Highlights Magazines while my brother and sister and dad would go back. But my dad figured out that he could call. I could call and talk to her from the pay phone in the waiting room, and I can remember, I don't remember if I was standing on a chair to talk on the pay phone. But I remember the pay phone feeling so high up on the wall. I had never used a payphone before, and it seems I didn't know what to say. I was out in the waiting room where it was filled with other kids who couldn't go back into the hospital.

Kate: They just left you out there?

Mom: Well, he came, you know. He came. He would go back and see her, and then he would come back and arrange the call, you know, because he'd have to put money in the phone and dial the number for it to ring in her room so I could talk to her while and while she was still in the hospital. Then we had my grandmother came and stayed with us when she first came home from the hospital. It was quite a while before she went back to school. I think that this happened during my school year, and it was quite a while before she could come back and start teaching again.

But I remember as we found out, as it came unfolded to me or revealed to me that she had cancer as when I was a kid, like 3rd or 4th grade. It was kind of a secret like a family secret, and we weren't to talk about it. And she didn't want anyone to know. And it seems like I remember them explaining to me. People at that time didn't know how cancer, somebody got cancer.

And it was a very fearful disease and felt like, you know, but what if you could get it from someone else? And also she was worried about losing her job as a teacher. If the school district knew that she had it, and I don't even know if they had medical insurance back then. I don't know at what point medical insurance became a common thing or a part of your workplace, you know, provided by your workplace. I never really knew about that, but then she was in pretty good shape up until about the time I was in 7th grade. At that point, the cancer had entered her bones. But actually, I think, what gave her a boost. I think that that gave her maybe a couple of years, like through 5th grade and in 6th grade

She did go to Sloan-Kettering Cancer Institute in New York City. A doctor that she knew there in Kansas City, I guess, had read about maybe a study being done, and she was willing to participate in this study, and so she was flown to, his is the first time for her to be on an airplane. My father had been because he had been on a plane during the World War II. But I remember this, the excitement of her getting to fly.

And we had an aunt and uncle and some cousins from Wichita that came and stayed with us, and they did it over Christmas. So, I remember that, they came just after Christmas. So, it was during Christmas break, and I think it was. I remember while they were there we went to see the movie Bambi, too. That was one event that happened during that time. This surgery was done by a doctor called Dr. Posianis and they had took out her pituitary gland. They thought that by taking out the pituitary gland it would slow the growth of cancer. So, my brother said it was supposed to give her about three more years, and it did, is how he explained it. So, she had that done in the winter. And then that summer we, my mom and dad and my older sister and I, drove to New York City because she went back for a checkup.

And at one point I did. It took me a while to even figure out how to spell the doctor's name, but later on in life, I did try to do some research on that doctor, and if there had been what the study was about, and I did. It took a lot of research, but did find the doctor listed and that this was a study that was done to see, but it didn't have good results. It wasn't like a promising results, but it was a.

Kate: Wasn't that doctor a woman?

Mom: It was a woman, which was very unusual, and it was, and my mother was so proud about that, that she had a doctor that was a woman. She, they made friends with a couple, a woman that she shared the room with, who were Jewish, and had been in the concentration camps. They made friends with the wife and the husband because the, I don't remember their names at all, but I know that they exchanged letters for a while afterward, after the first surgery that happened in the winter before we went back in the summer. And we met up with that family, and they had a daughter maybe close to my sister's age, and she took us, my sister and I through Greenwich Village. I remember that. I felt like in my mind she was Joan Baez.

Kate: Oh, my God.

Mom: That was how she looked, you know.

Kate: Wait, so how old were you then?

Mom: I was just coming out of 6 6th grade. Yeah, just out of 6th grade. So I was 12.

Kate: Oh, man, yeah. And this was in like, 1961 or something?

Mom: Yeah, something like that

Kate: Man, what a time to be in Greenwich Village.

Mom: I know, and well, I do remember that. Oh, West Side Story had just come out and I remember, as we walked the streets, looking for signs of the sharks in the jets.

Kate: Because they were real!

Mom: I really felt like they were real, and I was right there possibly see them.

Kate: Yeah. Oh, they’d just bust out into song.

Mom: Well, it was such an it was an amazing trip. I remember my dad well, because my mother was in the hospital having these, you know, checkups done, these checks done on her to compare. I guess you know, like what the results of that experimental surgery was. And I remember he took us to the United Nations and how he explained what the United Nations were to us, and I can remember standing outside the building, and seeing that statue of the gun that has, what would you call that?

Kate: Knotted up or whatever?

Mom: Yeah, it's the knotted gun. And being so impressed with that, and my father being so impressed and loving the fact that it was people from all over the world that came to discuss and problems that the world had in a way to get everybody's voice involved, and how we went into the to the room where you could put on headphones and hear what was being said in all these different languages. And it just, I don't know. It was very important. I knew I was seeing something really.

Kate: What an experience, yeah.

Mom: It really was, I mean, from our little town. To see an experience like that was pretty, very amazing.

Kate: And then you took me there later.

Mom: That's right.

Kate: In college. I don’t know if it was just me or maybe Austin was there.

Mom: Well, I think it was just you and I. That time we took the train down.

Kate: Yeah.

Mom: And spent the day walking around, because to me I wanted to kind of recreate what I was, what I remembered seeing as a child, you know.

Kate: Did your mom ever have like chemo? Or just these surgeries?

Mom: Chemo didn’t exist then.

Kate: It didn't exist yet, then?

Mom: No, she had treatments called cobalt treatments, and those were done in Kansas City, and we had, I remember we had our two-tone 1956 Buick at that time, and so after school. So this was probably during my 5th grade year, and part of, and maybe most, some of my 6th grade year, where after a few, maybe once a month, she would say, “I have to go for a treatment.” So, she and I would drive over after school, and the place that she went to was an office right across the street from the Kansas City Public Library, and I knew the library was there. It was huge. It took up one whole block, but I was not to get out of the car.

I remember going in with her once, and it was just, it was such a dismal kind of office where she was, with straight back chairs. I felt safer in the car, so I would often just sit in the in the car with the door locked with my homework and do my homework while she was upstairs while she was up getting her cobalt treatment

And the cancer, did change her in that she was very tired from it, and after teaching she always would come home and lay down before she'd get up to start dinner. I can remember that, too. It was a real shift kind of in family life during those years. And then during my, I think it was my 7th grade year that by then she was taking a, you had to take classes every once in a while to renew your teacher's license, and she was taking a class in Orff music which is interesting, since I have two grandchildren.

Kate: What did you say?

Mom: Orff. O-R-F-F.

Kate: I don’t think I’ve heard of that.

Mom: Well, it's interesting to me because that's what Sofia, and that's what our, my youngest granddaughter and grandson that they have in their school. It was, I don't know the first name of Orff, but it was like a music theory, a way of teaching, style of teaching music to children in it. I know it uses, uses a lot of folk songs from different countries, simple little tunes, and she was taking a class in that, and she fell. It was at wintertime, and I think my dad had to drive over and get her at this because she was taking this class at an evening class at, I don't know somewhere outside of Liberty. And he had to drive over and bring her home, and she was in so much pain that night. The doctor came to our house and gave her a shot of morphine. I can remember that. And then the next day an ambulance came without its license, its lights on, and came and picked her up and took her to the hospital, and she had broken her leg so her leg she had to have some surgery for her leg, but my father told us later that he was told that it shortened her leg, and she would not be able to walk again, you know, because her legs would be two different lengths, but she never did. She was always in a wheelchair after that.

So the last few years, couple of years of her life, we had a hospital bed in the house. But she stayed at home and then, so she passed away when I was 14, the last day in 9th grade, the last day of school of 9th grade. There weren't. The cancer was not. Now, I feel like I know so many people that go through that. But at the time it wasn't. I don't know if maybe if it was harder to detect. So maybe people did die of it, but we didn't know that's what it was. I don't know.

Kate: So how did your life change then, after she died?

Mom: Well, it changed dramatically. You know it was probably throughout my life the most frightening thing I'd ever been through.

Kate: Yeah.

Mom: And it also seemed like a thing I was observing, you know, because all of her care toward the end all kind of took place between my dad and my sister, and we had a housekeeper then that that would help out during the day. And I was mostly just an observer. It seemed like during all that time, but that happened in the end of May, and then my sister was in college then, and was engaged, and she got married at the end of that summer and moved out, moved into married student housing at the college where she and her husband were enrolled in school, and my brother was, he was off at college, and he got married that fall. So, it went from kind of a family setting to just my dad and I for the next, you know. I remember how different it was to come home and nobody was there. Just me. It was a weird feeling, but it also was a freeing feeling of being alone in the house. I can remember that sense, you know.

And suddenly being able to do things without asking permission, seemed so, so different. I can remember my dad and I got really close during those years. We would go shopping together and pick out, TV dinners had just come out and TV dinners with desserts. They had just started adding a little dessert to the TV dinners. So, we would we go to the grocery store and get our cereal and milk, and then go over to the freezer section and pick out our TV dinners.

Kate: Oh gosh, that was all you were eating?

Mom: Well, it was a great deal of what we're eating. It's still, I mean, there were people that would bring us dishes and stuff, and I occasionally would try my hand at something in the kitchen, but I had never been the helper in the kitchen. It always was my sister that was relied upon to do that kind of things. I was a dishwasher and a dish dryer and putter away of things, but never somebody that mixed things or helped make things. That was always her role.

So, and we ate out some, but not a lot because there weren't that many restaurants to choose from, and restaurant food was never, to me as I grew up, considered as good as homemade food. You know. We just didn't eat out too much, maybe Sundays or after something special if we went to the city, went into Kansas City, then we might go to a cafeteria or something. But I remember those years as growing very close to my dad.

Kate: And you had some really good friends, too, right?

Mom: Yeah, I did. Yes, I did within a year. And yeah, I met a good friend that I'm still good friends with my sophomore year. I know I've told you this, that when I would go to school in the fall every year, I'd always look for the new kids because our little town was, to me, so boring. It was so routine, it was so well known it was over. It was just.

Kate: You knew everybody.

Mom: Like a rerun. It was just like watching reruns all the time, and I would always look for the new kid, you know, something exciting and new. And my sophomore year, here came the new kid from Gary, Indiana, who did not want to be in Liberty, Missouri. And so we forged a really good friendship because she did not want to, she wanted to go back to her hometown and was miserable, being there, and I was miserable as it was. So, the two of us together became really good friends, and still are good friends all these years later.

Kate: What kinds of stuff did you do together?

Mom: Oh, talked on the phone mostly. I remember that year, the year I turned 15, my father gave me my own phone line, which was very unusual back then. But he did, I did have my own little princess phone, so I was able to talk on the phone all I wanted, though, my friends were never in that situation because they had to still share their phones with their families.

Kate: Was this when you were still at your old house before you had moved?

Mom: Yeah, that phone was installed on our old house, so that was the year I turned 15. So that would have been the fall of my sophomore year. So she died in the spring, very end of school my freshman year. So, by fall, you know, he did a lot of things then. He said yes to a lot of things that he would not have said yes to if my mother was still there, I guess. And I can say that he really spoiled me during those, that was a sweet spot time of my life.

And then you know the story that he began dating. My mother had been my grade school music teacher. He began dating my high school music teacher and that was very different for me. But they ended up getting married my junior year and built a new home. So, we moved out of my childhood home into this new home, and my phone came with me. I already had the phone.

Kate: Tell us about when this, when you called yourselves the Rejects.

Mom: Yeah. Well, there were three of us that became really close friends the end of my sophomore year, and all through my junior and senior year. And we were sort of good girls, but we also were very rebellious, and we kind of embraced the sixties, I guess, is what you could say, and had our own little subculture, our kind of, you know how kids will do that when they're teenagers. They'll have their own language, their own jokes. We all were kind of rebellious against our parents, but not terribly, openly, badly rebellious, but just enough.

The way we became we started calling ourselves the Rejects is because, one of my friends had a little brother that was probably about 8th grade, 7th or 8th grade, and we really teased each other a lot. To us, everything was funny, and we were teasing him one day out in the driveway of her house. I remember he got so angry, and he just yelled at us. “You all! You're all just a bunch of rejects!”

And we just embraced that. We said, “Yeah, we are! You're right.” So, we started calling ourselves, referring to ourselves as the Rejects. And then, finally, we just ended up getting work shirts, those blue work shirts, and had our name, “The Rejects” put on the back of them in these iron-on letters that were kind of shiny, you know, rubberized letters, but they were the color of like a yellow pencil, that kind of yellow. I remember that, and they were in an arch on the back, and we would wear those like to school. Well, we do dances or and we were, do you know, going to things around town? The three of us together would have our reject shirts on, and I wore it to school a few times, but it really, really, really upset my stepmother when I had that shirt on at school.

Kate: Right, and she was very, very strict teacher.

Mom: She was an extremely strict teacher.

Kate: Choir teacher, right?

Mom: She was beloved by a lot of the kids, I would say. 95% of the kids in our high school just loved her because she was kind of a fashion maven, and very tall and thin, always wore dyed to match everything, and she was very kind of tall and elegant, and she'd never been married before. So this was her first marriage to my father.

But she really worked the music, this was vocal music, and she really worked the kids hard, but in contests, they would go to state contests and district contests. Her groups always got fours. You were ranked one through four, and her kids always came back with fours. And I was in her music group. I mean, when my mother was still living, she and my mother did know each other because they were both music teachers in the school system. And you had to try out when you went into high school, you had to try out audition for this and I was kind of pushed to audition for it. I didn't see myself as doing this, but music had been a big part of my childhood, and through my mother. And so, I did try out for it. There were four freshmen girls chosen for it. I don't know how many freshmen boys, but there were only four of us in there, so it was all upperclassmen to me, upperclassmen kids I didn't know. It was very nerve-wracking for me to be in this this class, this a capella class, and performed with them throughout that year. And then the end of that year we had to, or it may have been during that year, we had to try out for small groups, and so I was in sextet, small girls’ sextet, also, so I had to do sextet practice with her after school.

And I knew her because she had also attended our church, and when I was in 3rd grade, I had done a solo in our church, the Carol of the Questioning Child at our Christmas programs. She had been the angel that was saying, it wasn't exactly like a duet. But it was like a call and response, where as they as the carol of the questioning child I was singing out, you know, questions about Jesus’ birth. “Where was Jesus born today?” And she would sing out as the angel who would respond, “In a manger far away.” And we had to practice all fall for that program. It was a big deal in our church. It was like a whole service of music, and my mother was asked to have me do that solo by the woman who was the wife of the president of the college in our small town, William Jewel College, because her daughter had sung that same solo when she was a little girl, and so she wanted to hear it again at that Christmas program. So, they asked my mother if she would have me do it. So, I spent months practicing that at our home and then had to go down and practice with this music teacher, the high school music teacher, who then, it turned out years later, became my stepmother. It was just kind of ironic.

Kate: That was weird. Did you sing it from the balcony, or something like that? Or was she up in the balcony?

Mom: No, we were. No, we were on the you remember being in that church. It's a huge, big sanctuary. We were up on the stage.

Kate: Oh, okay.

Mom: Yeah. I was singing in a primary choir up on this stage we had little chairs, and so my little primary choir had a song to sing, and then everybody else was to sit down, and I was to remain standing, and then they were going to go into the Carol of the Questioning Child. And I'm pretty sure we were accompanied by my mother on the piano for that, and the little kid next to me didn't realize that I was going to be doing this, and kept pulling on my choir robe to try to get me to sit down. And I was yanking on my robes, saying, trying to whisper, “I'm supposed to. I'm supposed to,” you know, when we went into it. I had to do it twice. I had to do it once on Sunday morning and once on Sunday evening because so many people came to that performance. The church was just packed but it was one of the most scary things I think I did, had to do as a child.

Hadley: I want to ask what were like that you guys talk about to this day the Rejects. What were some of most famous Reject stories that you guys have?

Mom: Oh, my gosh! I can't believe you would ask me to share these!

Hadley: What's one that you guys always talk about?

Mom: Well, there was one where we got in trouble at a restaurant in our little town. It was kind of like a pizza place, and we went. We were driving around. My friend had a, I think it was we were in her car. And she had a Rambler, and we had been driving. You have to realize in the sixties was kind of a car culture. So when kids got the car for a Friday night or a Saturday night, they literally stayed in the car almost the whole evening, just driving around. So, we drove around the square, drove around the college, drove around, and you'd see other kids, and you'd wave in the car and maybe pull over and get out, and whatever.

But this time, we had stopped at this little restaurant and went in to use the bathroom.

We locked the door, and we stayed in there forever because we were putting on makeup and doing our hair and kind of horsing around. We called it horsing around back then, to horse around was kind of to goof off and be silly, and people kept knocking on the door. We were not opening the door, and finally one of the waitresses or something came over. I don't know if she had a key or whatever, but she was so angry at us and told us that we were causing a fracas. That was the first time we'd ever heard the word fracas, and so after that, we used that word as much as we could and always referred to that as the fracas or would accuse each other of causing a fracas just to make fun of the whole situation. But because of the word fracas, I remember they had a gravel parking lot, and when we when we drove out, my friend, who was driving stirred up a lot of gravel in the parking lot as we left.

And another one. I shouldn't tell this at all, but it was kind of how my little town worked. We had the college boys in this town were called squirrels because the college was up on a hill and was filled with trees, and so they were called the squirrels. And that's how you differentiated a town boy from a college boy was you'd say he's a squirrel, meaning he lived up on the hill in the trees. And so there were two boys that we knew that actually were from New Jersey and were students there, and we were out with them one night, riding around in the car, and they were older. We were in high school. They were older, and one of them had an ID. I don't know that they were 21 but, was going to go into a liquor store and get some liquor. And so as we drove, we dropped them off, and then we were driving around while they went in, the town policeman saw us and followed us in the car and pulled us over. Well, where they pulled us over was kind of a very main street of town right in front of a car lot. And the car lot had a string of lights that were strung on a wire in front of the cars, and they had us all lined up there while they searched the car.

Kids were driving by on the street and honking at us as they went by, and what had happened was, when we went around the block, I think we saw the policeman and we didn't pick our friend up. We just kept going, so there was no liquor in the car, and we were let go. But then we went back around and we met up, and it became a big story. Well, the thing is, when each one of us got home a few hours later, every one of our parents already knew about this incident, had been called. I don't know how they knew.

Kate: The police.

Mom: But either yeah, by the police or by kids that saw us. Or people from our town that saw us. But there literally was nothing you could do.

Kate: That's a real social network there.

Mom: It is, it is! There was nothing that you could ever do.

Kate: Rapid speed!

Mom: That would not get back to your parents. There was like no way things couldn't get back in this little town, you know, and that was a big deal for me, having a mother and stepmother that were teachers and my dad a minister.

Kate: What was that thing about, like a brick in the wall that you would hide things?

Mom: Oh, my gosh! I forgot about that. Yes, yes, on this little, on the way up the hill to this college, there was a little house that had a stone wall that was like a Civil War stone wall where the rocks were just laid together. They weren't cemented together. One of our friends, her older brother had gotten us a fifth of gin, I think it was, and so we were going to, but we had to have a place to keep it. It was a thing that was going to last a long time, but we had to have a place to keep it. But nobody could take it home.

So, I said, “Well, let's hide it in that wall up there.” So, we went up and ended up pulling away some of the rocks and found a place in there that we could make a little niche in the wall to hide this bottle. At that time, we were all in senior English. I think the name of the poem was “The Flower in the Cranied Wall,” or else that was a line in the poem. I think it was by Lord Byron. It could have been that, I should look that up and see. But we always refer to that as the flower in the cranied wall. Well, it turned--

Kate: The code name for the gin.

Mom: The code name for the gin was the flower in the cranied wall. Well, it turned out that that little house belonged to a guy that was a basketball player at the college, and was also a student teacher at the college at our high school, and somehow he heard about the flower in the cranny wall and he went out and got it. So we lost it. We lost it. Yeah, he found it.

Kate: Oh, that's too bad!

Mom: Yeah, it was too bad.

Kate: Since you mentioned poetry, I wanted to ask, you read a lot in high school I think, right?

Mom: I did. I remember asking for a typewriter maybe my junior year and got one. And I took typing my senior year. Actually, I wasn't going to. It never crossed my mind. I wasn't going to do anything that might make me end up being a housewife or an office worker, so I never took home ec in high school, even though all of my friends did, and they all have wonderful stories about their home ec classes. I kind of refused to take it because I thought that would, it was like getting a brand of you were going to be a homemaker. And the other thing was, if you took business or shorthand or typing, I thought well, that meant you were going to be a secretary, and I had far greater dreams for myself than that. I really thought I was going to grow up and be a writer. I wasn't going to do anything that would hold me back from that.

But then while I was in high school, and I guess somebody heard me say that. My friend said, “Well, aren't you going to college?”

And I said, “Sure!”

And she said, “Well, you better take typing because you're going to have to type your papers,” which never even occurred to me, because in high school you handwrote an essay. If you had a paper due, you handwrote your essay. It could be 3, 4, 5 pages long, but it was handwritten. And so I did end up taking typing. It may have been my junior year that I did that because I remember typing a lot of things I wrote during my senior year, and I ended up with a little column in our high school newspaper, which was sort of a free verse little column. I also worked on our student news, our yearbook too, so I had journalism classes and took forensics, things like that, and debate. I remember taking debate. I was terrible in debate. I didn't understand what I was even getting into.

But anyway, I was trying to. I was trying to plot out a different path for myself. And even shen it came time to pick college colleges, I applied to a local college or a college that was in Missouri. It was a state school in Missouri, and I just assumed I would go there because I was definitely getting out of town. There was no way. My sister attended the college in our local town, but there was no way I was going to do that. And suddenly, when I heard how many other kids in my class had applied at that college, it was just like, Oh my God, I can't have college just be an extension of high school. I have to go where I'm brand new and my life can be brand new, and I can meet new people.

I asked my dad about going to the college he had gone to Oklahoma Baptist University, which was in Oklahoma, because it was out of state, and you didn't have to pay out-of-state tuition. At the same time, I hadn't had the opportunity really to mourn my mother and the loss of her very much right after she died. It was more like I was kind of in a state of shock after that and did everything I could to keep myself from thinking about it.

I think which is why I was so close with my friends, and kind of bury myself and activities of involving them, staying busy, you know.

So, he was delighted that I would choose that, and so I ended up going to school down there, and I really know in hindsight part of that was to sort of resurrect her. To be in the same dorm where she was and the same classrooms there. There were new buildings that had been built since she had gone, but I knew some of the older buildings were the same ones that she had been in.

My freshman year, I was actually only in the freshman dorm for just maybe about a month because they had over overpacked, overcrowded that dorm, and I was staying actually in what was called a guest room which is where they put visiting professors or families, if parents came for the weekend or something, and it wasn't on a dorm hall. It was off of the parlor part of the building of the dorm, and it had its own bathroom, which was very unusual, because everybody else shared one in the hall, but they wanted to get that room available again. Kids enroll in school and can drop out, you know, and shifts happen within the first month or so. So, when a space came up in the upperclassmen dorm, I was moved over there with another freshman girl, and we spent the rest of the year in that upperclassman dorm.

But I knew when I was first there that I was in the same dorm that she was in. I didn't have any idea what room she was in, but I can remember walking the halls and thinking about her being in the same hallways and wondering if they had black and white linoleum all down that was what the halls were on all three floors were paved with or floored with. I remembered thinking, I wonder if that same linoleum was there, and it had such great woodwork. It was just a beautiful, beautiful dorm, and it was on the oval part of the campus. You pulled in and drove down a long oval. It was right on the oval.

I knew these stories of my mother going home on the weekends, and then on Monday morning when she was going back to school, my grandfather would make her ride in the grocery truck that was making deliveries from the wholesale house, and so she would have to ride back to college in the front cab of this grocery delivery truck. She was always so embarrassed about that. She just hated that, hated going back to school in that truck.

My father had also told me that this campus was surrounded with rock walls and it was kind of on the, I believe, the north edge of the town it was built in, in Shawnee, Oklahoma. And when he was there, these rock walls were sort of the edge of the campus, and he and my mother would sit out on the rock walls and watch the sunset and the sun setting in Oklahoma, and he had described this to me before I went to school there. Because of the dust in the air, these sunsets were beautiful. They were kind of probably like they are in Arizona. They're very red and fill up the whole sky. So they, I would do that. Sit out, being there.

And there were several people professors that were there that she had been in class with that that had gone on, and that remembered her and knew my father, you know, when he was there. But that's really why I ended up going to school there, I think. Because it was far away from Liberty.

Kate: There were a lot of rules there, though, for women. I was very shocked by this.

Mom: Oh, yes! Well, yes, it was very different than had I gone to the state school because women had a curfew. You also had to always wear a dress. Women had a curfew. It was either 9 o'clock or 10 o'clock on school nights during the week, and weekends, I think, was midnight. It may have been midnight, 11:30 or midnight, and

I ended up getting in with a really fun bunch of girls there, too, that were older than me because I lived on their hall, the hall of the dorm. But they were kind of rebellious, and I seem to always seek out the rebellious kids that are not coloring in the box, those that colored outside of the lines.

We ended up with sort of a little core group of these girls, and we all had trench coats. Trench coats were very popular by then. And a trench coat, I don't even know if you guys know what that means to have a trench coat, but it's a coat that you could wear in the rain, but it didn't have a hood on it, but it was waterproof, and was kind of an off-white canvassy color, usually with a belt that tied at the waist, and they were about the same length as a dress. So, we would wear those trench coats with our cutoff shorts underneath. So, that was how we would go around campus wearing cutoffs and not be in trouble was because we just would always have our trench coats on. So we were like a trench coat club.

Kate: And something about going to dinner, where you had to have a certain number of people.

Mom: Oh, of people, yes. Well, there were two places you could eat. One was in the girls’ dorm, where I was staying, and that was family style, and in order to eat family style, you had to have six people at your table. So, you would have to gather together as six people that would go down and eat, and everything was served family style for those six. We could also go over and eat in the boys’ dorm. In the basement of the boys’ dorm was another cafeteria where you just was like a regular cafeteria, so we always walked over there and ate. It was like the nice girls that went downstairs and ate family-style.

Kate: And actually, they had bed check, right?

Mom: Oh yes, they had bed check.

Kate: A woman would come around and make sure you were in your bed. That’s crazy.

Mom: Yeah, I know, I know. The lights would flicker, too, because lights were out like at 10:30 or something like that, and bed check was a little bit after 10pm. Maybe we had to be in at 9pm, and bed check was at 10pm. And each dorm, each floor, or every so many rooms. I forgot what they were called, but they were kids that this was their job, like their student work job. Kind of be the person in charge of that end of the dorm, and they would have to do the bed check at night.

Kate: Oh, they did it. Okay.

Mom: Yeah, yeah, where they would. And so this was at a time when girls wore falls, which were kind of like half wigs that would fit on the back of your head. And so everybody, or any girl that had one of those, also had a little form that it sat on on their dresser, and the form looked like a styrofoam head, a bald head, and so they would stick their fall onto the.

Kate: On the pillow. Yeah. Well.

Mom: They would see, stick it onto the head form with these little pins, and so if somebody was sneaking out of the dorm at night, they would borrow somebody's head and stick it in their bed with either the fall on it. Or if you rolled your hair with rollers at night, there were these little cloth caps that you would put over your roller so they could stick the cloth cap over it, and then they’d turn it sideways toward the wall, so it would look like they were asleep in bed.

Kate: How did you sneak out, like you just?

Mom: Well, you wouldn't come in. You wouldn't come in, and then your roommate would cover it for you. You couldn't sneak out. You'd have to already be out, you know. I mean, that didn't happen very often, but it wasn't. Or if or if you were in some other part of the dorm, you know. We had another thing that we did where we went up in the attic at night. This dorm had an elevator in it, the kind that I think you had one in your elevator at Vassar that had a --

Kate: Like a lever thing that you?

Mom: It had a gate that swung across.

Kate: Yeah, yeah.

Mom: And the gate had to be closed in order for it to engage, and it was notorious for people to take the elevator and leave the gate open, and then whoever needed the elevator would have to walk up and down all the steps to find it. But we would take the elevator up to the attic, and it was the older girls that knew about this part of the of the dorm that was an open space that the elevator would go up to, and when you got up there were lights in the attic, and it was a concrete floor that had painted stalls with room numbers painted on the stall.

Kate: Like for storage?

Mom: When you came to school, you could put your luggage up there, or your boxes that you moved in, and a lot of those had stuff that was left over, that kids had graduated, but never.

Kate: Just left.

Mom: Yeah. So, there was one little corner of the attic that was made up into a smoking corner that had old chairs. Kind of like reading chairs that had been drug over into this corner and crates and a lamp. And so there was kind of like a little group of us that occasionally go up there and just talk the night away, up there in the in the attic.

Kate: What happened with the phone incident?

Mom: Oh, my gosh! Well, kids played pranks.

Kate: Yes they did.

Mom: And so, this was a prank that was my roommate.

Kate: A pretty genius prank.

Mom: It kind of was, but it was long and involved, and I can't even believe that I got involved in it because it was so complicated to do. But my roommate who was from Oklahoma, she was the one that was the barrel racer, who was the Oklahoma state barrel racing queen one year. Her father worked for Southwest Bell, so she knew how telephones worked. You know the whole thing, and this is when there were no phones in any rooms.There was one phone in the hallway for every so many rooms, and if you were calling out or your parents were calling in, they would call that line, and whoever was around would answer it and then have to go look for the person and get them to come answer the phone. So, my roommate knew that if you unscrewed, well, the phones at that time had handles, one for your ear, and one for you to a speaker part that you spoke into. She knew if you unscrewed the speaker part of it, the phone. I didn't, most people don't even know that that unscrews, but it does, it unscrews. And she knew that there was a little disk in there that I guess was like the microphone that your voice went through to be amplified and go into the wires. She knew that if you took that out and put the phone back together. If you answered it, no one could hear you.

So, she got the idea that we should go around. This was at night, like in the deep, dark early. You know, everybody was asleep and the hall lights were off. The only lights that were on were the exit lights that glowed down the hallway. She had the idea that we should go around and collect all of those, and this was, I believe, on a Saturday night, so it would have been on a Sunday morning that people woke up and discovered the phones didn't work, so we went around and unscrewed those and collected all of them, and she had a Kotex box that we put them all in, and then we set them down in the front office of the dorm.

Kate: Oh!